First Visual Art Center American Art and Ww1 Madonna and Child

Helm Robert Posey and Pfc. Lincoln Kirstein were the first through the small gap in the rubble blocking the ancient table salt mine at Altausee, loftier in the Austrian Alps in 1945 as World War II drew to a close in May 1945. They walked past one sidechamber in the absurd damp air and entered a second one, the flames of their lamps guiding the manner.

At that place, resting on empty cardboard boxes a foot off the ground, were eight panels of The Adoration of the Lamb past Jan van Eyck, considered i of the masterpieces of 15th-century European art. In ane panel of the altarpiece, the Virgin Mary, wearing a crown of flowers, sits reading a book.

"The miraculous jewels of the Crowned Virgin seemed to attract the calorie-free from our flickering acetylene lamps," Kirstein wrote later. "Calm and cute, the altarpiece was, quite just, in that location."

Kirstein and Posey were two members of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Athenaeum section of the Allies, a pocket-size corps of mostly heart-aged men and a few women who interrupted careers as historians, architects, museum curators and professors to mitigate gainsay damage. They found and recovered countless artworks stolen by the Nazis.

Their piece of work was largely forgotten to the general public until an fine art scholar, Lynn H. Nicholas, working in Brussels, read an obituary well-nigh a French woman who spied on the Nazis' looting operation for years and singlehandedly saved 60,000 works of art. That spurred Nicholas to spend a decade researching her 1995 volume,The Rape of Europa, which began the resurrection of their story culminating with the movie,The Monuments Men, based upon Robert Edsel'southward 2009 book of the same name. The Smithsonian's Athenaeum of American Art holds the personal papers and oral history interviews of a number of the Monuments Men every bit well as photographs and manuscripts from their time in Europe.

"Without the [Monuments Men], a lot of the nigh important treasures of European culture would be lost," Nicholas says. "They did an boggling corporeality of work protecting and securing these things."

The Monuments Men

In a race against time, a special forcefulness of American and British museum directors, curators, art historians, and others, called the Monuments Men, risked their lives scouring Europe to prevent the destruction of thousands of years of civilization by Nazis.

Nowhere, notes Nicholas, were more than of those treasures collected than at Altaussee, where Hitler stored the treasures intended for his Fuhrermuseum in Linz, Republic of austria, a sprawling museum complex that Hitler planned as a showcase for his plunder. On that first foray, Kirstein and Posey (portrayed in pseuodyminity by actors Bob Balaban and Beak Murray, respectively) had also discovered Michelangelo'due south Madonna, which was spirited out of Bruges, Belgium, past the Nazis in September 1944 every bit the Allies advanced on the city. Within days, they'd besides constitute priceless works past Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer.

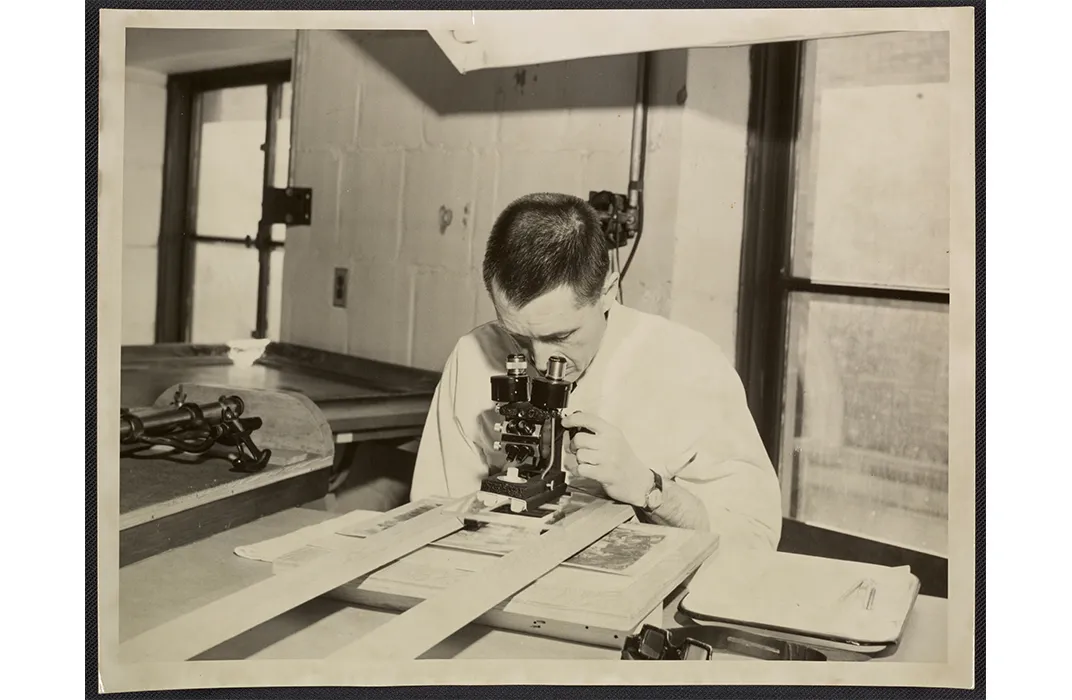

They summoned the only Monuments Man for the chore, George Stout, who had pioneered new techniques of art conservation before the war working at Harvard'southward Fogg Museum. Early in the war, Stout (given the name Frank Stokes equally played by George Clooney in the movie) unsuccessfully campaigned for the creation of a group like the Monuments Men with both American and British authorities. Frustrated, the World State of war I veteran enlisted in the Navy and developed aircraft camouflage techniques until transferred to a modest corps of 17 Monuments Men in Dec 1944.

Stout had been crossing France, Germany and Belgium recovering works, often traveling in a Volkswagen captured from the Germans. He was one of a handful of Monuments Men regularly in forwards areas, though his letters home to his married woman, Margie, mentioned merely "field trips."

Monuments Men similar Stout ofttimes operated alone with limited resource. In one journal entry, Stout said he calculated the boxes, crates, and packing materials needed for a shipment. "No risk of getting them," he wrote in April 1945.

So they made practise. Stout transformed German sheepskin coats and gas masks into packing materials. He and his small ring of colleagues rounded upwardly guards and prisoners to pack and load. "Never anywhere in peace or war could you expect to encounter more selfless devotion, more dogged persistence in going on, much of the time lone and empty-handed, to get information technology done," Stout wrote to a stateside friend in March 1945.

(Map designed by Esri)

The Allies knew of Altaussee thanks to a toothache. Two months earlier, Posey was in the aboriginal city of Trier in eastern Federal republic of germany with Kirstein and needed treatment. The dentist he found introduced him to his son-in-law, who was hoping to earn safety passage for his family to Paris, even though he had helped Herman Goering, Hitler'due south second-in-command, steal trainload after trainload of art. The son-in-law told them the location of Goering'south collection as well as Hitler's stash at Altaussee.

Hitler claimed Altaussee equally the perfect hideaway for loot intended for his Linz museum. The complex series of tunnels had been mined by the same families for 3,000 years, as Stout noted in his journal. Inside, the conditions were abiding, between 40 and 47 degrees and most 65 per centum humidity, ideal for storing the stolen fine art. The deepest tunnels were more than a mile inside the mount, safe from enemy bombs fifty-fifty if the remote location was discovered. The Germans built floors, walls, and shelving as well as a workshop deep in the chambers. From 1943 through early 1945, a stream of trucks transported tons of treasures into the tunnels.

When Stout arrived there on May 21, 1945, shortly later on hostilities ended, he chronicled the contents based on Nazi records: 6,577 paintings, ii,300 drawings or watercolors, 954 prints, 137 pieces of sculpture, 129 pieces of artillery and armor, 79 baskets of objects, 484 cases of objects thought to exist archives, 78 pieces of furniture, 122 tapestries, 1,200-one,700 cases patently books or like, and 283 cases contents completely unknown. The Nazis had built elaborate storage shelving and a conservation workshop deep within the mine, where the chief chambers were more than a mile within the mountain.

Stout likewise noted that there were plans for the demolition of the mine. Two months earlier, Hitler had issued the "Nero Decree," which stated in function:

All military send and advice facilities, industrial establishments and supply depots, equally well equally anything else of value within Reich territory, which could in any way be used by the enemy immediately or within the foreseeable future for the prosecution of the war, will exist destroyed.

The Nazi district leader nearly Altaussee, Baronial Eigruber, interpreted the Fuhrer's words as an order to destroy whatever objects of value, which required the sabotage of the mines and then the artwork would not fall into enemy hands. He moved eight crates into the mines in April. They were marked "Marble - Do Not Drop," but actually contained ane,100 pound bombs.

His plans, however, were thwarted past a combination of local miners wanting to save their livelihood and Nazi officials who considered Eigruber's program folly, according to books by Edsel and Nicholas. The mine director convinced Eigruber to set smaller charges to augment the bombs, then ordered the bombs removed without the district leader'southward knowledge. On May 3, days before Posey and Kirstein entered, the local miners removed the crates with the big bombs. By the time Eigruber learned, it was too tardily. 2 days later, the small charges were fired, closing the mine's entrances, sealing the fine art safely inside.

Stout originally thought the removal would take place over a year, but that changed in June 1945 when the Allies began to set the zones of mail service-VE solar day Europe and Altaussee seemed destined for Soviet control, pregnant some of Europe's neat art treasures could disappear into Joseph Stalin's hands. The Soviets had "Trophy Brigades" whose job was to plunder enemy treasure (information technology'due south estimated they stole millions of objects, including Onetime Master drawings, paintings, and books).

Stout was told to move everything by July 1. Information technology was an impossible order.

"Loaded less than two trucks by eleven:xxx," Stout wrote on June 18. "Too slow. Need larger coiffure."

By June 24, Stout extended the workday to 4 a.m. to x p.thou., but the logistics were daunting. Communication was hard; he was frequently unable to contact Posey. In that location weren't plenty trucks for the trip to the collecting point, the sometime Nazi Political party headquarters, in Munich, 150 miles abroad. And the ones he got oft broke downwards. There wasn't plenty packing textile. Finding food and billets for the men proved hard. And it rained. "All easily grumbling," Stout wrote.

Past July 1, the boundaries had not been settled so Stout and his crew moved forrard. He spent a few days packing the Bruges Madonna, which Nicholas describes as "looking very much like a big Smithfield ham." On July 10, it was lifted onto a mine cart and Stout walked information technology to the entrance, where it and the Ghent altarpiece were loaded onto trucks. The adjacent morning Stout accompanied them to the Munich collecting point.

On July 19, he reported that 80 truckloads, i,850 paintings, ane,441 cases of paintings and sculpture, xi sculptures, 30 pieces of article of furniture and 34 large packages of textiles had been removed from the mine. There was more than, merely not for Stout who left on the RMS Queen Elizabeth on Aug. 6 to render to home on his way to a 2d monuments bout in Japan. In her book, Nicholas says Stout, during just more than than a year in Europe, had taken 1 and a half days off.

Stout rarely mentioned his fundamental role candidature for the Monuments Men and then saving endless pieces of priceless fine art during the war. He spoke about the recoveries at Altaussee and ii other mines briefly in that 1978 oral history, but spent most of the interview talking about his museum work.

But Lincoln Kirstein didn't agree back to his biographer. Stout, he said, "was the greatest war hero of all fourth dimension – he actually saved all the art that everybody else talked about."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-monuments-men-180949569/

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/1b/041b7782-384d-46a9-98b4-98f04517febf/aaa_howethom_44942.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/fb/d1fbcdbd-8e5e-4970-9746-e23b16c18d6d/aaa_howethom_44938.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/43/27431862-08c8-4b53-8ddb-af16200f4222/aaa_howethom_44934.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/cd/dacd4526-94f6-4777-8925-5e54a06c0a8d/aaa_howethom_44936.jpg)

0 Response to "First Visual Art Center American Art and Ww1 Madonna and Child"

Post a Comment